New Fashion, New Jewelry

May 24, 2015

Every piece of art jewelry on view in the Driehaus Museum’s latest exhibition, Maker & Muse: Women and Early 20th Century Art Jewelry, is a stunner in its own right. But this is not art in a vacuum; not jewelry for jewelry’s sake.

That’s because even the most artistic jewelry in the exhibition was meant to be worn. Which makes it subject to inspiration from several things, all of which the jewelry maker must consider. First, there are the unique properties of the person who wears it—her physical palette, like the curvature of neck and chest, shape of a popular hairstyle, the bone structure of a wrist—as well as a series of social intangibles: What is the woman saying with the jewelry she wears? Is this piece—and the woman who wears it—bold and captivating, demure and delicate, lavish and heavily adorned, or flowing and unfettered?

Finally, jewelry isn’t typically designed to be worn on the body alone. All the way back in Shakespeare’s time, as Polonius said to Laertes, “the apparel oft proclaims the man.” Or as we put it today, “The clothes make the man”—or woman. Fashion has often served as a marker that helps define a person’s place in the world and their relationship to it. Jewelry adorns and complements clothing, and the two perhaps have a closer relationship than any two crafts could.

In this post, we’ll explore how art jewelry—a term invented later to describe a wide variety of bold, genre-breaking jewelry being made all over the world around the turn of the 20th century—also has a story to tell about transformations taking place in women’s fashion during this period.

This was especially prevalent in Britain. Progressive women began sporting alternative fashions called “aesthetic dress” or “artistic dress,” taking place within a larger dress reform movement known as “rational dress”. Some had dedicated themselves to spreading the word about health dangers of tightly laced corsets, while others sought a fresh fashion for a new century. Reform styles rejected the bustles, hoops, and corsets that were de rigeur in Victorian times, and the new dresses—popular especially within designer William Morris’s circle, which included the Pre-Raphaelites—had high waists, flowing skirts, and billowing sleeves inspired by the Renaissance. They were looser, practical, and infinitely more comfortable—and yet completely romantic and boldly stylish.

As fashion began to change, jewelry had creative opportunities to meet new needs. Cloaks and capes became popular, for example, offering modest cover as women dared to go without her corset in public. So you have accessories like the cloak clasp, like the one you see here by husband-and-wife pair Edith and Nelson Dawson, evolving alongside this trend.

Attributed to Edith Dawson (English, 1862-1928)

“Birds in the Trees” Cloak Clasp, c. 1900

Silver, enamel

Collection of Richard H. Driehaus

In Austria at this time, Emilie Flöge—a designer and lifelong companion of painter Gustav Klimt—designed her own loose, avant-garde reform clothing and paired it with jewelry made by the Wiener Werkstätte. The workshop was devoted to the idea of a total work of art, called Gesamtkunstwerk, achieving a completely harmonious interplay between one’s outfit, jewelry, and even home interiors. Floge’s fabrics were often designed and made by the Werkstätte, so that unity between fashion and jewelry was established even before Floge cut her cloth.

Emilie Louise Flöge (1874–1952)

Emilie Louise Flöge (1874–1952)

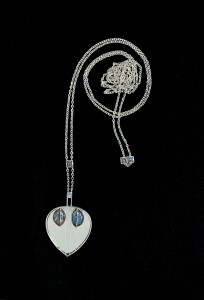

Wiener Werkstätte (Austrian, 1903-1932)

Pendant, 1904

Silver, opal, mirrored glass

Private Collection

The long necklace Floge wears in this photograph was purchased for her from the Wiener Werkstätte by Gustav Klimt. The heart-shaped pendant is of silver, opal, and mirrored glass, and designed by Wiener Werkstätte co-founder Josef Hoffmann.

There was great diversity in the art jewelry that emerged to pair with reform clothing around the early 20th century, but the theme was the always same: freedom. The strictures of heavy ornamentation and tight corsets fell away, and so too did the social binds that previously fixed women in place. This freedom allowed women to wear what they felt was both beautiful and comfortable; to pair these fashions with handcrafted jewelry that was bold, independent, and artistic; and confidently step out of the to vote, work, and contribute to the public sphere in exciting new ways.

Freedom and social change as seen through the ways we adorn ourselves is a fascinating topic, and it’s one we’ll be exploring further in an exciting new exhibition. Dressing Downton: Changing Fashion for Changing Times opens at the Driehaus Museum on February 9, 2016. Featuring more than 35 costumes from the hit period drama Downton Abbey®, the exhibition chronicles the tumultuous early 20th century in Britain through the lens of the latest fashions, both upstairs and downstairs. You won’t want to miss it! For more information, check out the exhibition website.