Out at Last: The Great Chicago Fire of 1871

October 10, 2012

On the morning of October 10, 1871, the flames had finally stopped. What was left was, well, hardly anything. About a four-mile swath had been cleared in two days, everything was in ruins, and the conflagration would go down in history books as an infamous disaster for this new, bustling city: the Great Chicago Fire.

There are plenty of great resources online that tell the whole story, like GreatChicagoFire.org and the Chicago History Museum’s History Files. The Chicago Tribune also has a brief account here. What follow are illustrations from Harper’s Weekly in 1871, which attempted to capture the fire’s scope and devastation in a way that words sometimes cannot.

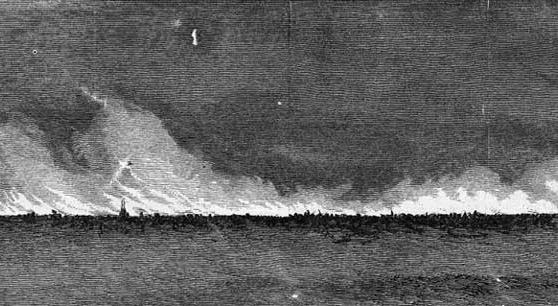

First, the publication portrayed the fire and the panic it caused as it spread from the southwest side to the rest of the city.

The aftermath, all of those iconic buildings and businesses in ruins, was also documented. Here are two that would have been particularly relevant to the family who once lived in the Driehaus Museum, the Nickersons. First, the Crosby Distillery, owned and operated by Samuel M. Nickerson’s cousin, Albert Crosby. Crosby provided the leg-up for Nickerson to make his own start in liquor distilling in Chicago, which earned him his first fortune.

And the First National Bank Building, a beautiful landmark by Burling & Whitehouse. Nickerson was president of this bank for 30 years, and commissioned the same architectural firm to build the Samuel M. Nickerson Mansion in place of the wooden home he lost to the fire.

Then something remarkable happened—they put Chicago back together again. Immediately after the flames went out, new codes were instituted to ensure that this would be the last Great Fire. Next came the rebuilding. Chicago proved to be like the prairies it’s surrounded by here in Illinois—after burning away, fresh growth springs to life.

“What she has been in the past she must become in the future,” declared an optimistic William Bross, “and a hundred fold more.” The new city was planned with a more analytical eye, one that remembered mistakes made in the past and predicted that “hundred fold” future. The economy and population exploded. Immigrants came from all over for the construction work available and settled down, and their cultures continue to enrich the city today. New architectural styles abounded. There are some remnants of the fire—Clarke House, now located in the Prairie Avenue district, or the historic Water Tower Building on Michigan Avenue—that remind us of the city’s earliest days. But the true legacy of Chicago is located within that determined effort and creativity, that refusal to be daunted, that gusto that defined the years after the Fire and remains a deep part of its identity today.

All illustrations from Harper’s Weekly are via.