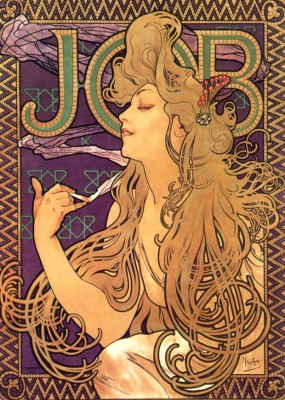

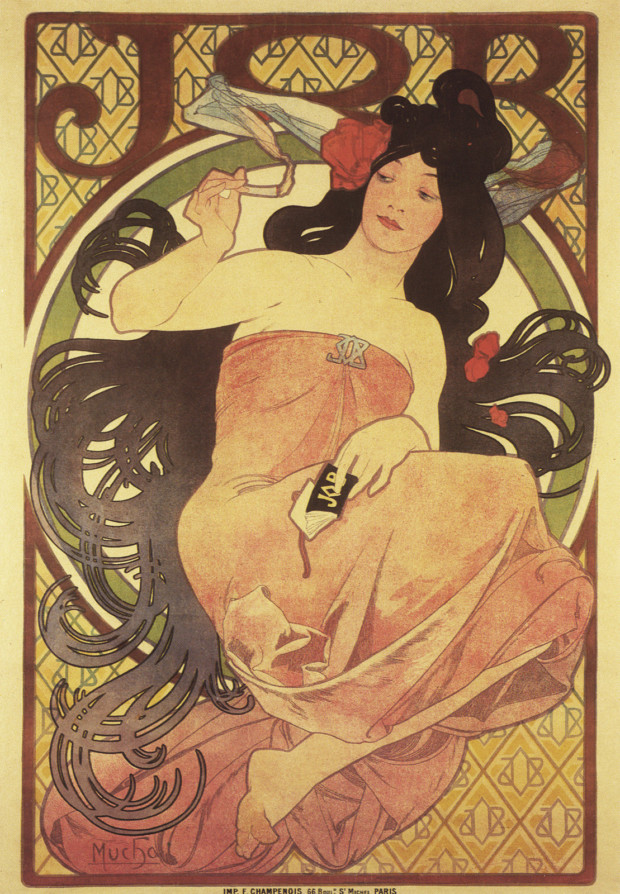

The Sensuous Smoker

April 20, 2017

The poster designer, Alphonse Mucha, was a Czech-born artist in his late 30s. He moved to Paris in 1887 seeking fame. There he mastered French Art Nouveau, an avant-garde style that stretched and elongated decorative lines and text into sinouous, vine-like tendrils that seem straight out of a fairy tale. In Mucha’s posters of women—from big-star performers like Sara Bernhardt to imaginary parisiennes—he often applied that Art Nouveau style to their wild, flowing, abundant tresses. These glamorous, larger-than-life posters helped define the place of the female in advertising in the industry’s earliest days.

Job is probably one of Mucha’s best known advertising posters. And it was radical at the time in its depiction of this glamorous woman enjoying freely an activity once reserved for men alone.

There is plenty of evidence that in ancient times, women might have smoked as openly as men. Tobacco was an integral part of Mayan religious rituals, for example. But sometime between then and the 17th century, female smokers in France, Britain, and America came to be seen as, at best, backwards or socially deviant, and at worst, vulgar and immoral. Appalachian mountain women, Breton peasants, or lower-class prostitutes smoked pipes; uneducated factory workers used snuff; and eccentric Bohemians smoked little cigars. In reaction to these stereotypes, a widespread social attitude dictated that respectable women shouldn’t dare associate themselves, however indirectly, with this supposedly unladylike activity. Wild claims about smoking abounded—it gave women mustaches, some said; it made them go insane; said others. In some American school districts, female teachers could be fired for smoking, while no such prohibition existed for men. In 1908, New York passed a law outright prohibiting women from smoking in public.

Women who did smoke—or wore pants, or worked, or rode bicycles—were satirized in cartoons in France and America as the ‘femmes nouvelles,’ or new women. It wasn’t a compliment. These women were breaking down boundaries that held rigid ideas of masculinity and femininity in place, and not everyone welcomed these bold changes.

But in Job, Alphonse Mucha makes smoking seem—well, sexy. This is no old-fashioned rural woman puffing on a little pipe, but an illustrious beauty enjoying a rebellious pleasure. In the early years of the 20th century, when women began agitating for equal rights, smoking—a male activity heretofore held back from women—became a way to subvert those oppressive social norms. By the 1920s smoking was seen as a chic, enlightened activity claimed by independent women who loved to socialize, dance in clubs, and enjoy their freedoms.

Other advertisements and photographs appeared around the same time, many of which were ushered along by a burgeoning tobacco industry that saw women as an untapped market with great potential. These helped continue to transform the smoking taboo into an act that proclaimed your independence, eased stress, and helped you lose weight. In 1929, Lucky Strike Cigarettes hired ten beautiful debutantes to walk, lit cigarettes boldly in hand, in New York’s Easter parade. Others hired famous admirable women, like Amelia Earnhardt, for advertisements. Moves like this followed Mucha’s Job posters in a radical redefining of what smoking could be for women—not deviant, but glamorous.

Today, of course, we have a new smoking taboo in our culture. But rather than being based on an arbitrary idea of what is appropriately feminine and masculine, this taboo is based on medical research showing the devastating health effects smoking has on all of us—men and women alike.

Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Women and Smoking,” 2001 Mar. A Report of the Surgeon General, Office on Smoking and Health.

Daily Mail, “Tobacco Traces on Mayan Flask Proves Race Did Smoke,” Gavin Allen, 11 January 2012.

Mucha Foundation, Poster for ‘Job’ Cigarette Paper (1896).

POPSUGAR, The History of Women and Smoking, Colleen Barrett, 11 June 11 2012

Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising