The Ship of Dreams

April 14, 2012

As we near the 100-year anniversary of a tragedy that shook an entire culture’s belief in its own bright, progressive destiny, some American teens have supposedly been surprised to discover that the RMS Titanic’s sinking was, in fact, real. (“I never knew titanic actually happened,” one tweeted. “Always thought it was just a film,” wrote another.)

I admit that at 11 years old, when James Cameron’s film Titanichit the theaters, I developed an aching crush on the young, debonair Leonardo DiCaprio in the role of Jack Dawson, a third-class passenger who turned a spoiled Gilded Age heiress’s world upside down, and that was about the extent of my interest in Titanic. But this fictional love tale (recently re-released in 3D) is just a proliferation of a nation’s century-long, unwavering obsession over a true and truly tragic historical event.

The Titanic sank in the early dawn hours of April 15, 1912, taking the lives of more than 1,500 people and a good-sized piece of the Gilded Age’s heady optimism with it. Stephen Spignesi, author of The Titanic for Dummies (yes, there really is such a thing), recently called this “one of those seminal events that changed everything.” Comparing the disaster to September 11, 2001, the New York Daily News wrote that it “marked the end of an era, ended complacent, more innocent centuries and ushered in darker times.”

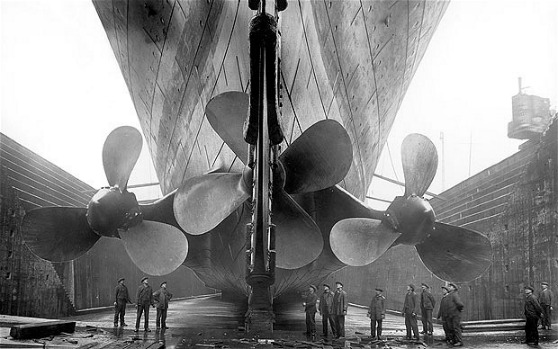

In many ways, the 19th century and first decade of the 20th stood for technological progress, industry, wealth, growth—all of these seemingly unchecked and unbounded. Then, the greatest ship minds or hands could make was rendered as useless as a child’s toy by an impassive iceberg and all anyone could do was watch, helpless.

Everything in the advanced industrial New World, from ships to families to maxims upon which society was built, proved to be more frail and vulnerable than imagined—which is to say, just as frail and vulnerable as before. Humanity has always been subject to the beatings of accident or Nature while simultaneously toiling to get out from beneath them, building shelters, cities, rails, ships, and agricultural innovations. It is when the battle begins to tip in our favor, as it had by the early 20th century, that the truth—that we can never quite, for all our efforts, stop a plane crash, tornado, nuclear disaster, or war, to name a few from recent times—comes as a particularly hard blow.

After the Titanic sank there was little time to recuperate, build a bigger ship just to spite it, or regain any great measure of optimism, because a historical timeline after 1912 reads like a litany of disaster. 1914, World War I breaks out in Europe and America joins the fray a year later. 1929, the stock market crashes, ushering in nationwide financial ruin and the Great Depression. 1930s, a series of severe dust storms caused by drought and farming methods causes agricultural devastation across 100 million acres of America. 1939, World War II begins in Europe. 1941, a Japanese attack on American soil prompts us to enter the war and it starts all over again.

A New York Times headline on April 10, 1912 reads, “THE TITANIC SAILS TO-DAY. Largest Vessel in World to Bring Many Well-Known Persons Here,” and the first-class passenger list read like a Who’s Who of Gilded Age prestige: John Jacob Astor IV and wife Madeline, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidor Straus, Dorothy Gibson, Margaret Brown, J. Bruce Ismay, Frank Millet, Major Archibald Dutt, Henry B. Harris, Lady Duff-Gordon. A spread six days later on the front page of the Chicago Tribune screams, “LINER TITANIC SINKS; 1300 DROWNED, 866 SAVED. GIANT OF SEA RAMS ICEBERG IN ATLANTIC. Women and Children Taken Into Lifeboats while Men Remain. RESCUE SHIPS TOO LATE. Wireless Calls Summon Help, but It Arrives After Disaster. NOTED PERSONS IN PERIL.”

Today the prominently wealthy can conjure outrage—the 99 percent versus the 1 percent—or condescension, as innumerable reality shows prove a populace loves to roll its eyes at the lifestyle of Kim Kardashian. But the Gilded Age adored its wealthy. They were the good guys. They were paragons for American ambition and success and proof it was possible for you, too. Their wealth not only refined them but shielded them, sheltered them from a scratch-out-your-existence life that wasn’t far from an adolescent nation’s memory. So when Astor, Guggenheim, and others, supposedly immortal men on a supposedly unsinkable ship, perished, it proved the frightening fact that success is a thin shield indeed.

The newswire on April 15 delivered the worst news to a world holding its breath: no ship had reached the Titanic in time to pull its drowning passengers and crew aboard. The dispatch read, “Carpathia reached Titanic’s position at daybreak. Found boats and wreckage only.” A journalist, in a burst of poetry rare for newspaper reporting, wrote,

Some of that feeling was shared, I’m sure, by the people reading it at home.