World’s Fair Puck

November 01, 2016

In 1893, Chicago put on a fair that would awe the world. The World’s Columbian Exposition, so called in honor of the 400thanniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World, displayed the most fascinating innovations and arts of the period in one grand place. The fair organizers envisioned a 630-acre park, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted of New York Central Park fame, filled with bone-white neoclassical buildings by such eminent architects as Henry Ives Cobb, Richard Morris Hunt, Charles McKim, and Louis Sullivan.

Jackson Park itself was a wonder, and it also exhibited wonders. Visitors saw life-size reproductions of Columbus’s three ships, a 1,500-pound Venus de Milo made entirely of chocolate, a 70-foot tower of light bulbs, an 11-ton block of Canadian cheese, and the world’s first Ferris Wheel. The ‘Street in Cairo,’ a re-creation of the medieval city, immersed fairgoers in exotic Egyptian dance, architecture, and animals. Other cultures were likewise on display in attractions such as the Turkish Village, Dutch Settlement, Indian Village, Esquimix Village, Japanese Ho-o-den, Old Vienna, and German Village. Eadweard Muybridge showed the world’s first moving pictures, Louis Comfort Tiffany stunned with his magnificent chapel, and Frederick Pabst won a blue ribbon for his beer.

Puck—the first successful humor magazine in the United States, and at the peak of its popularity—also joined the world’s fair fray.

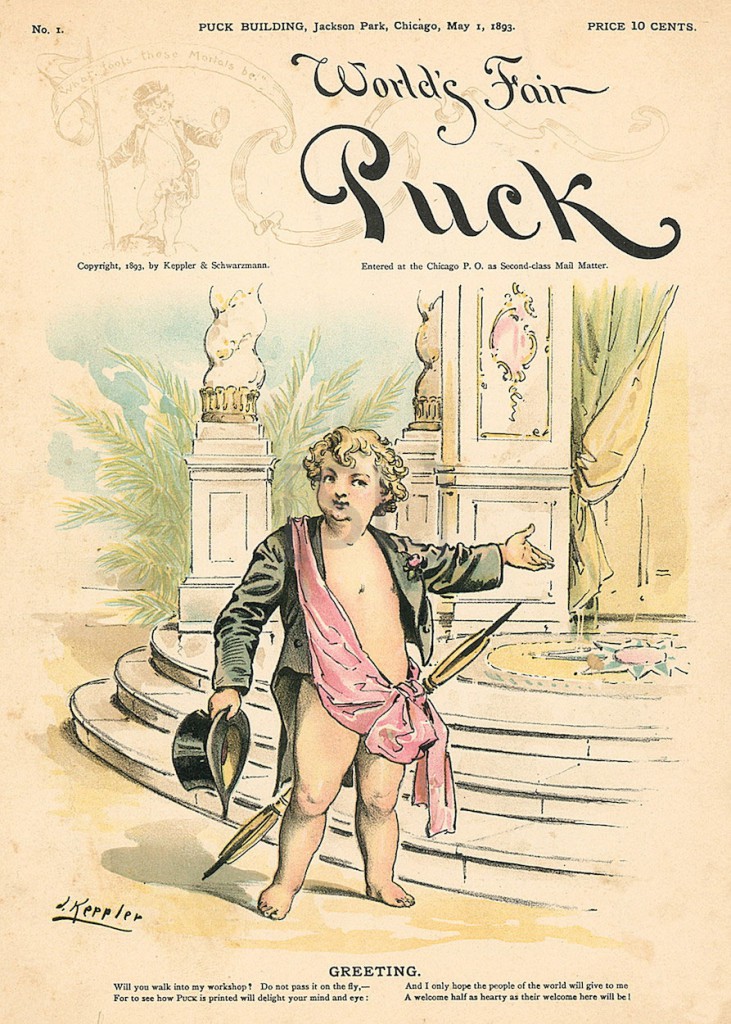

Puck positioned itself not only on the cutting edge of satire in America, but also on the cutting edge of printing technology. As the first magazine to print brilliant full-color cartoons each week, Puck showed off the emerging technique of chromolithography. So the fair organizers invited Puck founder Joseph Keppler and his partner, Adolph Schwarzmann, to give fairgoers an open-air demonstration of their process.

Keppler and Schwarzmann left New York for Chicago, launched a special World’s Fair Puck edition, and produced it on-site in Jackson Park, displaying their irreverent editorial style and chromolithographic technique for the fair’s nearly 26 million visitors. The fair organizers awarded Puck a central location in one of the “cheerful little pavilions” between the Horticultural Building and Women’s Building. Each week from May to October, they produced twenty-six issues from their McKim, Mead & White-designed Puck Building, while the parent magazine continued its regular weekly production schedule in New York.

Record, Photos from the Collections of the Avery Library of Columbia University and the Chicago Historical Society by Stanley Appelbaum, 1980.

At just twelve pages, World’s Fair Puck was about a third of the size of regular Puck. But each page packed just as powerful a satirical punch, with a few favorite themes that were revisited again and again.

The Country Boy in the Big City

The idea of an unwitting Midwestern “hayseed” bumbling around in the cosmopolitan world of Chicago provided plenty of laughs for readers.

But Keppler often backed the working classes against the rich, and couldn’t resist taking a shot at the fair organizers’ ticket prices. Labor unions had petitioned for the exposition to open on Sundays so working class families could attend. Even after a series of lawsuits resulted in the organizers’ agreement to the deal, few of Chicago’s factory workers could afford the price. World’s Fair Puck pointed out that “had you taken a microscope to aid you last Sunday, you would hardly have found a trace of the Workingman, whom Sunday-opening was expected to benefit.”

In a twist on this class theme, World’s Fair Puck poked fun at Midwesterners in general, depicting them as uncouth compared to high society in the Eastern U.S. In one issue, a Chicago hostess interviews a new butler. “Well, if, as you say, you lived in all the fin de siècle Boston houses, perhaps you may do for me,” she says. “But I must test you with a few questions first.” Her question reveals her inexperience, however: “In arranging the table for a ladies’ luncheon party, where would you put the toothpicks?”

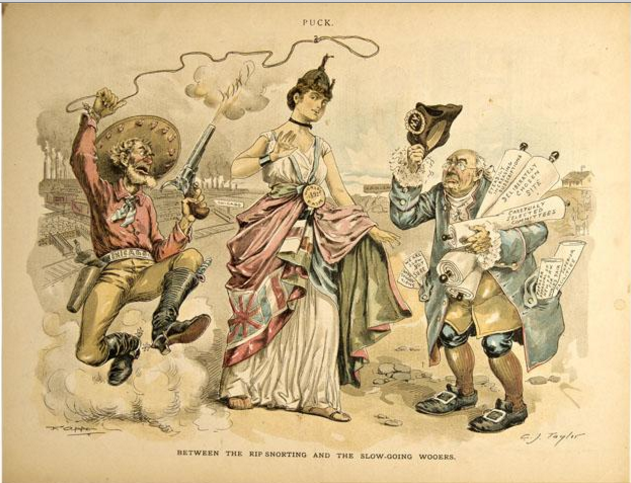

Chicagoans Versus New Yorkers

Chicago and New York competed fiercely with one another to host the World’s Columbian Exposition, so this theme was especially in force before the fair opened. The cartoon below represents the tussle between Chicagoans and New Yorkers for the prestigious honor, a Lady Liberty figure at center representing the fair. She stands between Chicago—the cowboy, left—and New York—the statesman, at right. Her preference for the statesman, with his carefully laid plans, is clear. But the wild Chicago cowboy lassos the reluctant World’s Columbian Exposition and ropes her in. The smoke from his gun contains the words “Wind.” New Yorkers thought smooth-talking Chicago politicians were ‘full of hot air,’ as the saying goes, resulting in the nickname the “Windy City.”

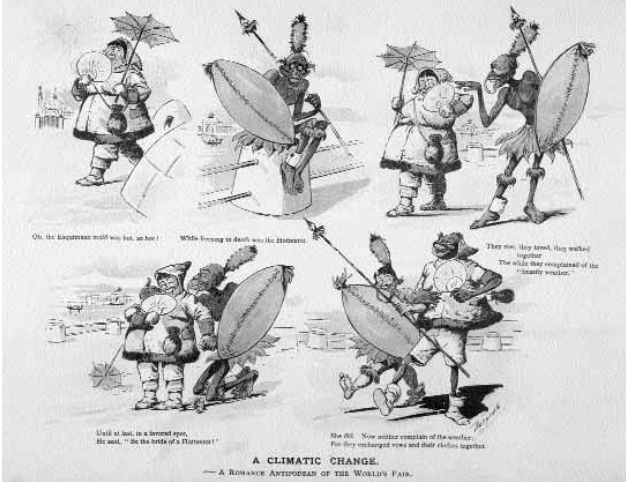

Anthropological Encounters

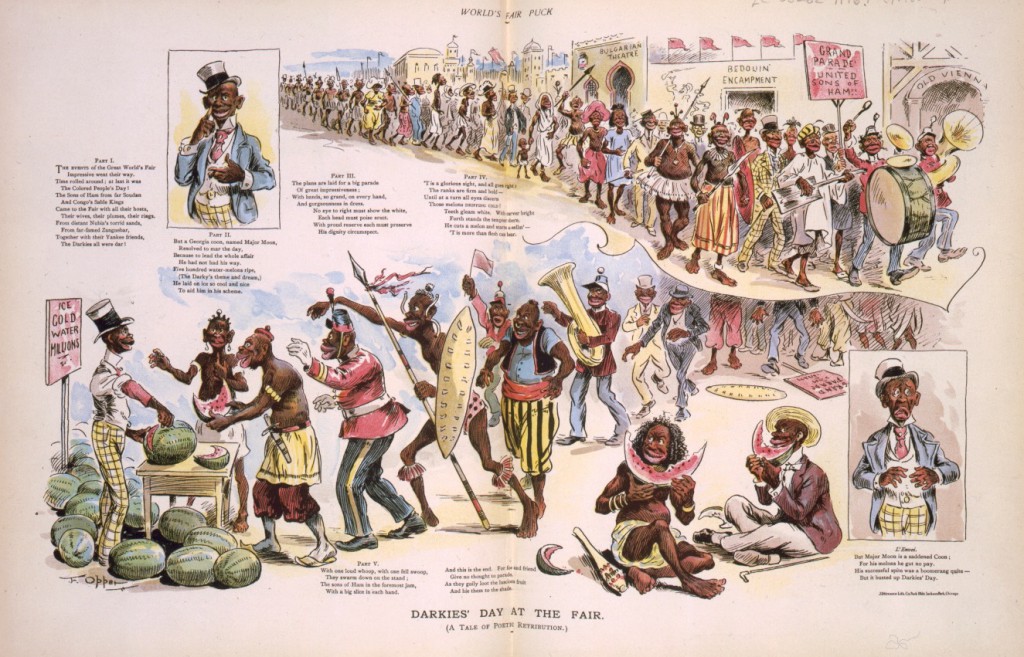

World’s Fair Puck made much of the inevitable strangeness and intimacy of Americans coming face-to-face for the first time with people brought from as far as Egypt, Benin, Java, or Alaska.

The fair made these exotic people into a kind of living diorama, showcasing their crafts, dress, architecture, and diet. World’s Fair Puck took easy shots when joking about the cultural differences, often leaving political correctness far behind. For example, one cartoon depicted a large Eskimo woman roasting in her furs during the hot Chicago summer, while a man from Dahomey (a now-defunct African monarchy), with only a leaf skirt and battle shield, shivers. Romance—and a costume swap—ensues, with the title “A Climatic Change.”

Others were blatantly racist. The cartoon below, entitled “Darkies’ Day at the Fair,” is an example of prevailing racism that placed people of color at the bottom of the social hierarchy and enforced cruel stereotypes.

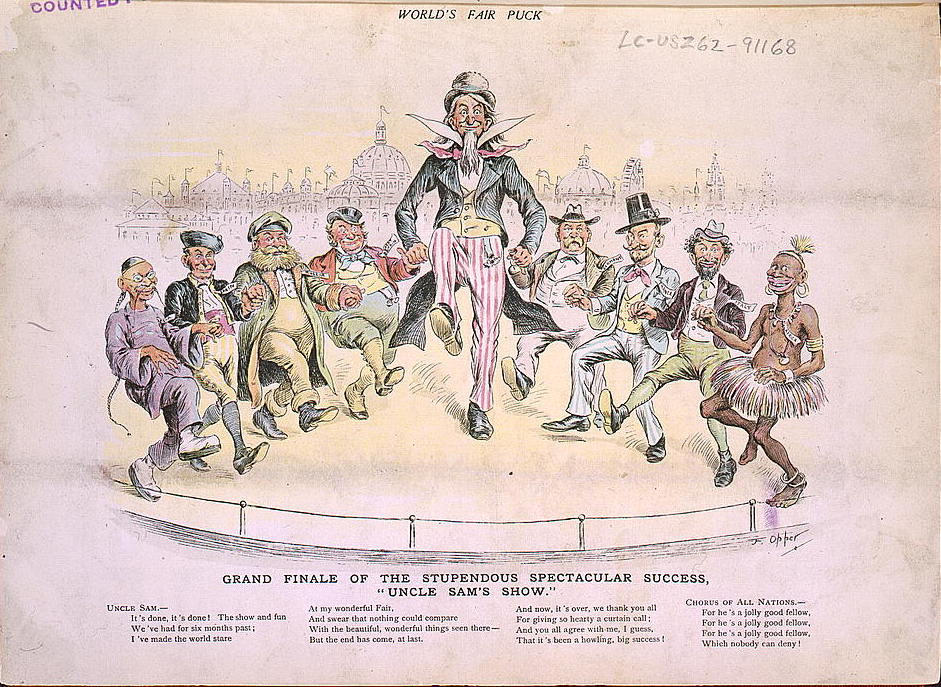

Hurrah for the Red, White and Blue!

Other World’s Fair Puck cartoons put biting humor aside for a moment to celebrate what brings us together. The Fourth of July and closing ceremonies were two occasions for patriotism, as you see in the cartoons below.

World’s Fair Puck would be the final innovation in Joseph Keppler’s career, although the parent magazine stayed in circulation until 1918. He worked at a feverish pace during the fair, amid working conditions that weren’t exactly ideal. Like the other Columbian Exposition buildings, the Puck Building was made of plaster, only meant to be a temporary, albeit grandiose, shelter for editorial and printing activities that summer. It was uncomfortably hot inside, and the tensions arose between writers and artists who were working while on public display. Keppler never recovered from the strain of the fair. He become ill with, according to his obituary in The New York Times, “a nervous disorder due to overwork,” and died in his home on the Upper East Side in February 1894.

RESOURCES

“Joseph Keppler and ‘Puck’” by Anne Evenhaugen. Smithsonian Libraries Unbound, December 12, 2012.

“Death of Joseph Keppler, A Noted Caricaturist and Part Owner of Puck.” The New York Times, February 20, 1894.

PUCK: What Fools These Mortals Be! by Michael Alexander Kahn and Richard Samuel West, 2014.

Coming of Age in Chicago: The 1893 World’s Fair and the Coalescence of American Anthropology by Ira Jacknis, Donald McVicker, and James Snead. University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

Perfect Cities: Chicago’s Utopias of 1893, by James Burkhart Gilbert. University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Popular Culture and The Enduring Myth of Chicago, 1871-1968, Lisa Krisoff Boehm. Routledge, 2004.

“The World’s Columbian Exposition”, The Chicago Historical Society, 1999.

World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, made available by the Paul V. Gavin Library Digital History Collection – Illinois Institute of Technology.

Zinc Sculpture in America, 1850-1950 by Carol A. Grissom. Associated University Presse, 2009.