[You Asked] Didn’t This Building Used to be Black?

October 04, 2012

You Asked…

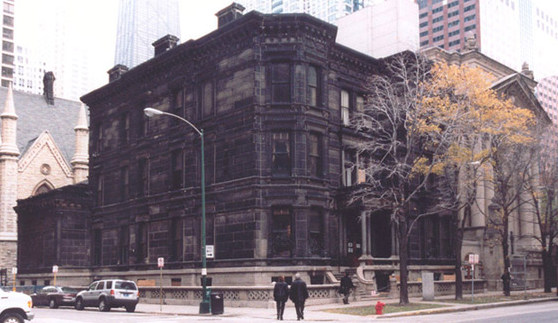

Didn’t the Nickerson Mansion used to be black? And how did conservationists manage to clean the exterior?

Today’s blog is part of an occasional series dedicated to answering visitors’ questions.This is an easy question to answer: 1. Yes, quite. 2. Very, very carefully.

(Oh—and with lasers.)

I can’t go on without pointing out first that the entire team of specialists who brought the Nickerson Mansion back to its original beauty—after it spent years holding up animal heads for Lucius G. Fisher, Jr…

…or fluorescent lighting for the offices American College of Surgeons…

—are pretty amazing. Although the exterior of the building is where we’ll focus our attention for now—and it was among the most impressive and groundbreaking components of the restoration—the team of more than 40 firms who worked on this house between 2003 and 2008 were each integral to the project. These experts of stained glass, lighting, decorative painting, wood, and fabrics continue to be an enormously helpful part of the ongoing restoration and care of this magnificent building.

That said, let’s talk about sandstone.

The Samuel M. Nickerson Mansion is constructed of sandstone and limestone, both native materials to the Midwest. Our sandstone, a yellow-brown sedimentary rock, came from Berea, Ohio. Being somewhat soft and easy to carve decorative elements into, sandstone has been a popular building material for domestic residences or cathedrals for ages. Plus, the stone is fireproof, a boon in the post-Great Chicago Fire days and, apparently, just good design standards. (“In too many Chicago houses expenditure seems to have run riot till the front stoop was reached when the easy step from the sublime to the ridiculous was made in wood,” wrote the Chicago Daily Tribune as a compliment to the wood-free Nickerson Mansion commission, in 1879).

Sandstone is also, unfortunately, made of sand. A soft and extremely porous material, as we all know, even when compacted by the millennia into stone. That presents two problems: one, when the city of Chicago is powered by bituminous coal—eight billion tons annually by 1890, to give you an idea—a porous stone will rapidly turn the same hue as the smoke billowing all over the city. The Tribune lamented in 1888, “What damage does the smoke of Chicago do to the architectural interests of the city? It does incalculable damage, both from an artistic and financial standpoint. What chance has any light color in Chicago?. . . There is soot everywhere.”

The second problem with sandstone is, when you come along in the year 2003 (which is when the Driehaus Museum was founded and when restoration began), those industrial pollutants had morphed into a kind of 100-year-old crust. In some places, that crust was 20 millimeters thick. It not the prettiest to look at, as you can see above, but it was also creating a kind of trap for water that would drip in between the stone and crust, then freeze, expand, and erode all of those lovely carved classical motifs.

Obviously, it had to go. But micro-blasting wasn’t going to work with such a soft material without seriously contributing to that erosion, so a series of tests were conducted by the Conservation of Sculpture & Objects Studio, which was contracted to save the façade. First, several types of chemicals were attempted on a test area of the building, ranging from mild to aggressive. Although in the flat areas this basically worked (although sometimes bleaching out the sandstone’s natural yellowish color), the detailing proved more difficult, and areas would end up in a range of shades. Then someone brought up the idea of lasers.

Developed in the 1980s to gently remove stains from the surface of sculptures, these lasers worked remarkably well when tested on the mansion. The process basically works like this: a beam of light from a handheld contraption is pointed at the building, and it breaks the molecular bond that had formed between the stone and pollutants. So the CSOS team spent more than a year moving slowly up and down the façade, clearing 20,000 square feet worth of black crust with the small handheld instruments. They finished in late 2005, two years after the restoration began. This was a particularly groundbreaking moment for historic preservation in this country—we are officially the first building to be cleaned by laser in North America.

We have a slideshow on our Preservation page on the website that shows some detailed in-process images.