‘Divine Sarah’: The Great Star of the French Poster

February 01, 2017

Young and stunning, with sculpted eyebrows and a head of rich brunette curls, French actress Sarah Bernhardt first captured the ardor of Paris’s theatre-going elite in the 1870s. The rest of the world’s attention inevitably followed. Admiring critics, resorting to poetic metaphor, likened her voice to pure gold, a nightingale, silver dawn, the stars and moon, and murmuring water.

She was in a class all her own—the Marilyn Monroe of the French Belle Époque. “There are five kinds of actresses,” declared American writer Mark Twain. “Bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses—and then there is Sarah Bernhardt.”

However gifted and alluring she was, stardom like Sarah’s isn’t made in a vacuum. One of the most captivating aspects of her presence actually occurred offstage, along the open boulevards of Paris. Striking promotional posters by Czech artist Alphonse Mucha catapulted Bernhardt from well-respected actress to international icon at the turn of the century, and have proved as lasting memories of her electric mystique. In turn, Bernhardt made Mucha a major success in the lively Parisian art world.

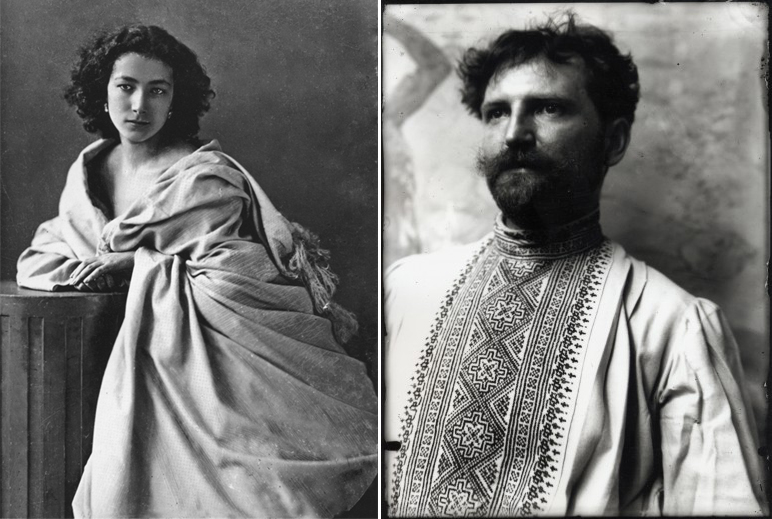

Sarah Bernhardt, about 20 years old in ca. 1864 (Photo by Nadar). Alphonse Mucha, self-portrait in his Paris studio, early 1890s (The Mucha Trust).

Sarah Bernhardt, about 20 years old in ca. 1864 (Photo by Nadar). Alphonse Mucha, self-portrait in his Paris studio, early 1890s (The Mucha Trust).The pair met serendipitously. Alphonse Mucha, a struggling Czech illustrator, was temping at the massive Paris printing firm Lemercier & Compagnie just after Christmas in 1894, while all the steady professional artists were away celebrating the holidays with their families.

Sarah Bernhardt approached Lemercier, desperate for a poster to promote her show debuting just after the New Year at the Théâtre de la Renaissance, a Greek melodrama called Gismonda. She was director and lead actor, playing a widow of the Athenian nobility who pledges herself to a commoner. Bernhardt needed the poster immediately, so Mucha, despite his lack of poster experience, was asked to draw something up for the esteemed actress. He came up with a stylized, monumental, full-sized portrait of the actress in a glorious empire-waist dress and gold-embroidered drapery, her face in dignified profile and crowned with orchids, grasping a palm branch. The lettering was architectural and exotic, mimicking Byzantine mosaic work. Mucha did what creatives in advertising firms still do today: take a real female human’s likeness and reveal a goddess.

Bernhardt absolutely loved it. A week later, billposters had plastered Mucha’s image all over Paris and Bernhardt had offered Mucha a six-year contract to design posters, stage sets, and costumes for her. Posters for La Dame aux Camélias (1896), Lorenzaccio (1896), La Samaritaine (1897), Médée (1898), La Tosca (1898) and Hamlet (1899) followed. Mucha designed them all with the same elongated, full-length format, almost like altarpieces—with Bernhardt in place of a saint. It’s no surprise she became known to her fans as ‘la Divine Sarah.’

Mucha’s images held Bernhardt’s likeness before the public imagination, and her fascinating performances burned her there. She is still considered one of the greatest actresses to have ever lived. “Something seemed to burn within her like a consuming flame,” said George Tyler, an American producer. “On the stage she loved and cried, not only with her soul, but with all her body,’ said Jules Lemaître, a French critic.

Sarah Bernhardt was born Henriette-Rosine Bernard, the illegitimate daughter of a Dutch Jewish courtesan, in about 1844. Her ambitions as a teenager to become a nun ceased when her mother’s lover put her onstage, where she found another kind of calling. She performed in works by some of the greatest playwrights of past and present: Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Jean Racine, Eugène Scribe, Voltaire, and Victorien Sardou. She played Cordelia, Cleopatra, Adrienne Lecouvreur, Phédre, Joan of Arc, Desdemona, Marguerite Gautier, and, daringly, Hamlet, as one of the first known women to perform the title role in Shakespeare’s tragedy. She appeared in silent films and lent her face to advertisements. She toured in Europe, the United States, Canada, South America, Australia, and the Middle East. She owned her own theatre, the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt, producing and directing plays as well as acting in them, and training young actors. She toured onstage and acted on film sets well into her 70s, and never retired—she was in the midst of a film project when she died. A few fragments of film and audio survive: here she is as Hamlet (video); as Elizabeth Queen of England (video); in Le Samaritaine (audio); and Phédre (audio).

Bernhardt was arguably the world’s first international star, setting a course for celebrity in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Predictably, her personal life was the subject of much fascination, and her adventures did not disappoint: there was an affair at age 20 with a Belgian prince resulting in an adored illegitimate son, Maurice; a duel proposed by gentlemen defending her honor from journalists; marriage to a foreign man 12 years her junior; an affair with a 27-year-old leading man at age 66; other affairs with the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), Victor Hugo, and other famous men. She injured her knee during a dramatic moment in a performance in Rio de Janiero and, as gangrene set in a year later, wrote another of her lovers, a great doctor, demanding her own leg’s removal.

In March 1923, Bernhardt died in Paris. She was 78 years old. Her death induced a worldwide lament. The L.A. Times published a somber announcement: “There is but one sentence today on the lips of Paris – ‘Bernhardt is dead.’ It has been uttered alike by concierges and Cabinet ministers, midinettes and princesses. One hears it spoken softly in cafes and whispered in churches.”

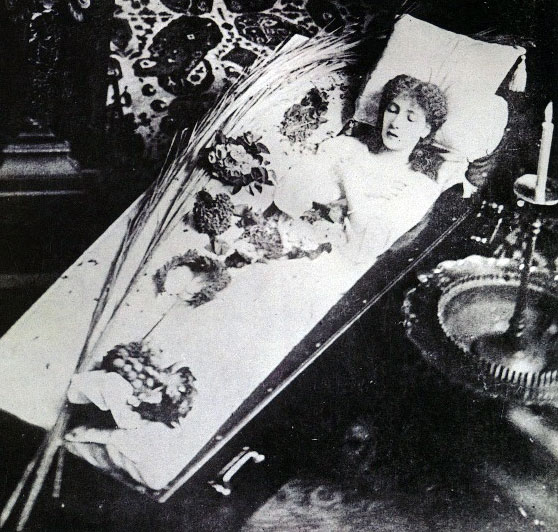

Her funeral, as you’ll see in this video, was a grand, majestic affair. Hundreds of thousands of devoted fans thronged the boulevards of Paris to mourn and pay their respects. For those unable to attend, one might purchase a memorti mori of ‘Divine Sarah,’, an Ophelia-like funereal photograph taken decades years earlier, in which the young actress poses, eyes closed and hands clasped, in the coffin she kept in her room.

c. 1880. Photography by Sarony.

c. 1880. Photography by Sarony.In death, as in life, Alphonse Mucha’s masterpieces–in which Sarah is monumentally, vibrantly alive–secured this great performer’s immortality in the cultural imagination.

…

Resources

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Sarah Bernhardt”

“Sarah Bernhardt’s Leg,” History Today, by Richard Cavendish, 2 February 2015.

Jewish Women’s Archive: “Sarah Bernhardt,” by Elana Shapira

“Face of Great Actress Subtle Even in Death,” LA Times, March 23, 1923

The Mucha Foundation, “Sarah Bernhardt”

“Sarah Bernhardt’s Dramatic Life, Onstage and Off,” NPR book review of Sarah by Robert Gottlieb, September 24, 2010, by Glenn C. Altschuler.