It Was Colonel Mustard With the Candlestick…

July 16, 2012 There is this great line in the book Great Houses of Chicago, 1871-1921, which I lugged from the shelf in search of insights on the popularity of conservatories during the Gilded Age. It begins, “The Victorians were notorious for collecting…”—and that’s a perfect enough start.

There is this great line in the book Great Houses of Chicago, 1871-1921, which I lugged from the shelf in search of insights on the popularity of conservatories during the Gilded Age. It begins, “The Victorians were notorious for collecting…”—and that’s a perfect enough start.

During the Gilded Age, wealthy Americans became collectors—of all kinds of things, but they especially favored expensive or exceedingly rare things like old master art, ancient books, and trinkets or handmade carpets from the far reaches of Asia. We call it conspicuous consumption today: an easy way of projecting visible identities using the things we buy and surround ourselves with. Today, a certain kind of car or wardrobe might earn cultural capital by aligning us with adored celebrities or wealthy tech visionaries, but at this point there were no movie stars or Steve Jobs types.

So we wanted to be European aristocrats instead.

The pricey trappings that went along with such an identity were vast private art collections, rare antiques collected abroad, adapted social customs such as the servant system, and architectural plans that folded old Europe’s aesthetic motifs with new American construction methods and conveniences. For that slice of time in the late 19th and early 20th century we call the Gilded Age, those high-end architectural plans often included the private conservatory.

“The Victorians were notorious for collecting,” write Susan Benjamin and Stuart Cohen in Great Houses, “and [Edward] Uihlein acquired plants.” (74)

Edward Uihlein, a wealthy brewer, settled in a beautiful residence on Chicago’s West Pierce Avenue during the late 19th century and there he

This was no mere personal hobby, but a luxurious, expensive, and laborious (for the servants who tended the plants, anyway) pastime that required traveling all over the world to find the most exotic species and bring them home again. Whether Uihlein collected out of a pure love of flora or not, it would have conveniently given others the distinctive impression of connoisseurship. This being what America’s nouveaux-riches were going for—that is, an impression that they were highly-educated, distinguished, eschewers of the low culture of common America, counted among the respectable old-money classes, etcetera—I’d say his penchant for collecting served him well. Accordingly, Uihlein rose to social prominence as a horticulturalist; he provided the Horticulture Hall at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition with most of its flowers and shrubs and in 1904 became president of the Chicago Horticultural Society. (74)

Lest we be too simplistic, however, there was more to the new fashion of private conservatories than just an urge to collect, nor was it solely inspired by a desire to build European-esque palaces with glassed-in gardens attached.

Increased industrialization in Chicago and the rest of the world, including Europe, for that matter, brought about a sort of nostalgia for the pastoral. Conservatories were like little in-house parks, continual reminders that nature was still out there while conveniently delivering its positive effects straight into the household. The plants grown there would serve to furnish various rooms of the house as decoration and to offset manmade things. Many people, then as now, believed that experiences with nature brought us closer to ourselves, to the spiritual world, to one another, to creativity, to what it means to feel fully alive. (See: Henry David Thoreau, Wendell Berry, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Annie Dilliard, Walt Whitman, anyone who thinks climbing Everest to be worth the danger, in my personal opinion, and, to bring us back to our Gilded Age time period, Aesthetic Movement tastemaker Owen Jones, who wrote in The Grammar of Ornament, “[The Creator’s] works are offered for our enjoyment, and so they are offered for our study. They are there to awaken a natural instinct implanted in us…”)

Yet one more reason for a private conservatory or greenhouse was due to the fact that when high incomes afforded higher-end lifestyles, interest in special meals—with exotic, gourmet ingredients and service to match one’s wealth—rose accordingly. Benjamin and Cohen write,

Needless to say, few conservatories survived their brief heyday. The Nickerson conservatory is gone, an auditorium in its place; the Pullman and Palmer mansions are long-since demolished; the Glessner conservatory has been renovated to provide an admittedly lovely event space. But Samuel Clemens’s Hartford, Connecticut house still stands, as does its modest conservatory where Mark Twain purportedly entertained his children with imaginary safari adventures among the plants. And George W. Vanderbilt’s famously massive Biltmore estate in Ashville included a Richard Morris Hunt-designed conservatory that is still open to the public every day of the year.

What others? Among the Gilded Age-era homes you’ve visited, have you found any with its conservatory intact?

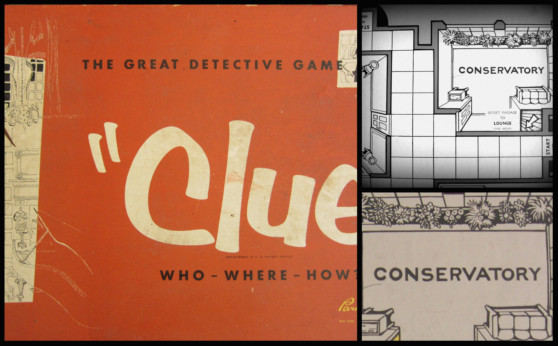

Notes: All quotes but for Owen Jones’s came from Great Houses of Chicago, 1871-1921 by Susan Benjamin and Stuart Cohen (Acanthus Press, 2008). Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament can be read in full here, thanks to the University of Wisconsin. I quoted him above from the essay preceding his final chapter, “Leaves and flowers from nature.” All images, excluding those of the vintage Clue game (which are my own), are details of photographs found in Great Houses of Chicago.