New York’s Historic Puck Building

September 01, 2016

This post is part of a series exploring the stories behind the Driehaus Museum’s latest exhibition, With a Wink and a Nod: Cartoonists of the Gilded Age.

The Puck of Puck magazine isn’t exactly Bacchus from ancient myth. Nor does he really resemble the “knurly limed, faun faced, and shock-pated” creature from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Rather, he looks like cherub dressed as up a Gilded Age dandy—complete with a top hat and frock coat. The coat is left wide open to expose his chubby nude figure, and in his hands he holds the keys to Puck’s reign of American humor: a fountain pen and a hand mirror.

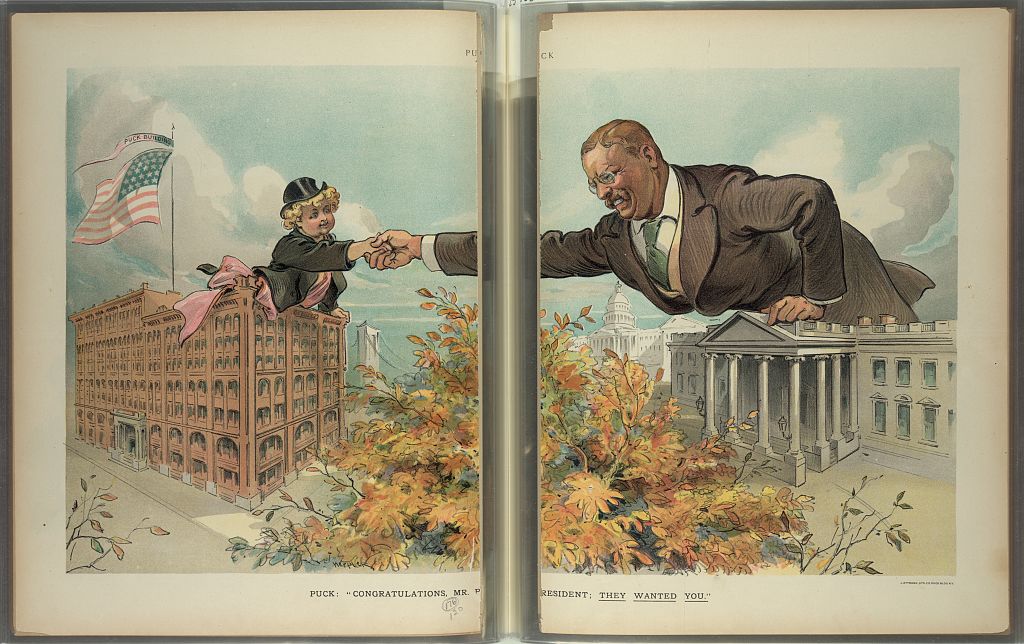

This is how Puck appeared in Puck magazine. This is also how he appears on the Puck Building exterior in New York City. Two gilded statues of this mischievous character still stand sentry outside the historic building, where, from 1887 to 1916, Puckturned out page after satirical page.

The Austrian-born publisher of Puck, Joseph Keppler, commissioned the building in 1885. He’d launched an English-language version of his small German satirical magazine seven years ago, and Puck had become a milestone in the history of American humor, with circulation hitting 80,000 in the early 1880s and climbing to 90,000 by the end of the decade. Riding the tide of success, Keppler, along with printer Adolph Schwartzmann and lithographer J. Ottman went in together on a property on the edge of the great publishing district of New York City. They hired German-born New York architect Albert Wagner to envision what would become one of the most iconic buildings in Lower Manhattan. The seven-story structure occupied an entire city block. King’s Handbook of New York City called it “the largest building in the world devoted to the business of lithographing and publishing, having a floor area of nearly eight acres.”

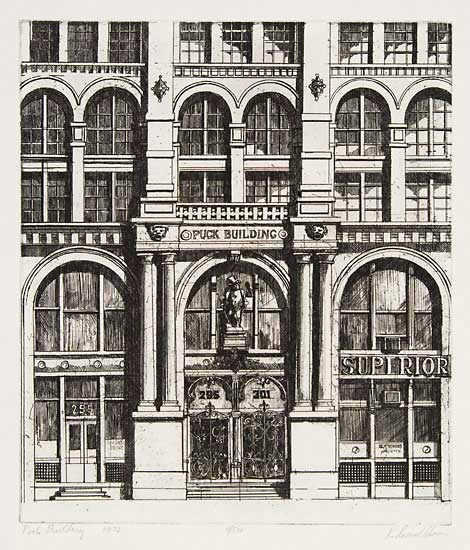

Albert Wagner worked out a design for Keppler that reflected a distinctly German style of Romanesque and Renaissance Revival architecture, called Rundbogenstil. The repeating arches—Rundbogenstil literally means “round-arch style”—and intricate brickwork are hallmarks of this short-lived but popular late nineteenth-century style. Romanesque Revival’s popularity is tied to Henry Hobson Richardson (a New York architect known in Chicago for the Glessner House), but Wagner’s Romanesque Revival is different from Richardson’s. Richardsonian Romanesque is a tad heavier, with rusticated stone and squat columns, while Rundbogendstil has smooth facades and an elegant lightness.

The massive brick building was constructed in three phases—the original structure was finished in 1885-86, expanded in 1892-93 to make more room for Puck printing, and altered in 1899 to make up for the intrusion of Lafayette Street into its footprint. Wagner closely supervised all three stages, giving cohesion to the building’s overall design. Seemingly endless arches of varying heights define three vertical sections of the façade, the richly colored brick contrasted by polished gray granite blocks, brownstone, and ornamental ironwork.

Little is known about Albert Wagner. He settled in New York in 1871 and worked for Leopold Eidlitz, a prominent Bohemian architect who may have passed his passion for Rundbogendstil on to his protégée. While Wagner never became as famous as Eidlitz, he kept up a busy stream of commissions for residential, commercial, and industrial buildings during his career. He died in 1898, leaving his firm and the final touches on the Puck Building’s last addition in the hands of his relative Herman Wagner.

The Puck team advertised their arrival in the neighborhood with typical tongue in cheek, topping off the building with statues of their mascot, larger than life and gleaming with gold leaf. Sculpted by Henry Baerer, the German-born artist known for his stern-faced bust of Beethoven in New York’s Central Park, the largest Puck statue stands above the building’s main entrance on Houston and Mulberry Street. (Another, smaller Puck is stationed above the Lafayette entrance.) The chubby sprite holds a hand mirror—the better to reflect society’s follies with—as well as a fountain pen. At his side hangs a book inscribed with his character’s jest in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “What fools these Mortals be!”

The building housed the Puck editorial team and the J. Ottmann Lithography Company, which produced the groundbreaking full-color images for Puck ‘s front cover, back cover, and centerfold. They were joined by a number of other businesses, including a bookbindery, hat frame manufacturer, electrotyping company, and hat shop on the ground floor.

Puck printed its last issue in 1918. So what is the Puck Building today? In 1980, Kushner Companies acquired the building for office and retail space. And in 2011, they got approval from the Landmarks Commission to transform the upper floors of the Puck Building into six penthouses—think Italian marble baths, mahogany-framed windows, William McIntosh floor patterns, televisions inside the mirrors. Luckily, the renovation preserved elements of the building’s original identity. The barrel-vaulted brick ceilings and architectural columns were left exposed, and Puck Penthouse’s brand style even borrows from the magazine’s masthead.

Want to learn more about the magazine printed in the Puck building during its heyday? Puck‘s illustrations changed the shape of American humor. Join us for next week’s exhibition lecture with Janel Trull, curator of the exhibition With a Wink and a Nod: Cartoonists of the Gilded Age, on Thursday, September 8.

SOURCES

Finn, Robin. “Penthouses for the Puck Building.” The New York Times, Sept. 19, 2013.

Gaiter, Dorothy J. “Restored Puck Building Opens Today.” The New York Times, Apr. 20, 1983.

PUCK BUILDING, 295-309 Lafayette Street, Borough of Manhattan. Landmarks Preservation Commission, April 12, 1983, Designation List 164. LP-1226. Accessed via Neighborhood Preservation Center. (neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb_files/1983PuckBuilding.pdf)

Puck Penthouses, puckpenthouses.com

“The Puck Building—Houston and Lafayette Streets”, Daytonian in Manhattan. 19 Jan 2011.